A Week in Area X

Sasquatch FAQ Series: Do Wood Apes Avoid Game Cameras?

Gray Wolf Killed in East Texas

Big Cat Conversations Interview Now Available

You can listen to the interview by clicking here.

Coming Home: I am Kickstarting the Blog

What Happened to Dennis Martin?

Catching Up: Previously Unpublished Black Panther Sightings

- Janene Thomas

Sasquatch Classics: The Leflore County Bigfoot War

The telling of scary stories around a campfire is a tradition that is likely nearly as old as mankind itself. While tales of ghosts, goblins, and murderous psychopaths can rattle the cage of nearly anyone, what better subject for a campfire story could there be than a cannibalistic and murderous sasquatch? The story of a haunted house might be creepy, but unless you are actually staying in the house in question it is easily and quickly forgotten once the marshmallows, chocolate, and graham crackers appear at the fire. Tales of a creature – a creature many people regard as being real – stalking the very woods in which you have pitched your tent, however, are not always so easy to put aside. One such terrifying tale is the story of a “bigfoot war” that allegedly took place in eastern Oklahoma during the mid 1850s.The story of the LeFlore County bigfoot war is one I have heard bits and pieces of through the years. I finally decided to look into the matter, gather as much information as I could, and make a determination as to whether the tale might have some truth to it or was an outright fabrication. Following is what I was able to find out.

It is said that in or around 1855, a band of Choctaws in what is now LeFlore County and farmers in what is now Arkansas were experiencing some terrifying events. It all began in a rather benign way with the theft of vegetables, a few head of livestock, and other foodstuff by stealthy bandits in the night. The thieves were cagey, quiet, and never seen. They were also smart, as somehow they never ventured into Choctaw encampments on nights when a watchman was in place. Neither did the bandits ever fall into the traps set for them by farmers outside of Indian Territory. Those charged with finding and capturing these marauders began to develop a begrudging respect for the wiliness of their adversaries as time went by and the petty thefts continued. While the thefts were annoying and did cause some hardships, neither the Choctaw or the neighboring Anglo farmers were afraid of the food bandits; however, things changed once women and children began to go missing.

Spurred by reports of these kidnappings, a group of 30 Choctaw cavalrymen was organized to hunt down the abductors. The group was led by Joshua LeFlore, a man of mixed Choctaw and French blood, who was deeply respected by his fellow tribesmen. Also joining the search party was a Choctaw warrior named Hamas Tubbee and his six sons. The Tubbees were huge men – all approaching seven feet in height and weighing in at more than 300 pounds each – and were regarded as fierce warriors and expert horsemen. The Tubbees were so effective in mounted warfare that despite their massive size, they became known as the “Lighthorsemen.” The contingent of searchers, armed to the teeth, set out into the region known today as the McCurtain County Wilderness Area to search for the kidnappers.

After riding all day, the searchers finally arrived in the area where they believed the bandits to be hiding. LeFlore brought his troops to a halt, stood up in his stirrups, and surveyed the area with a spyglass. It is unclear exactly what LeFlore saw but whatever it was, he ordered his men to charge toward a stand of pines roughly 500 yards distant. LeFlore and the Tubbee men led the attack. As the troops closed the distance between themselves and the stand of pines where the kidnappers were thought to be hiding, they were assaulted by a tremendous stench, the unmistakable odor of decay and decomposition. The horses of most of the men began to buck and rear, tossing their riders. Only the mounts of LeFlore and the Tubbee men were disciplined enough to remain composed, allowing the eight men to continue through the pines. As the men cleared the small wooded patch they came upon a large earthen mound. Scattered across the mound were the bodies of children and women in various stages of decomposition. LeFlore and the Tubbees caught a glimpse of a number of the murderers fleeing into the tree line on the opposite side of the mound. Only three of the killers stood their ground to meet the charge of the “Lighthorsemen.” It was at this time that the cavalrymen realized they were not going up against any human foe; rather, standing before them, snarling and beating their chests, were three huge, hair-covered creatures. Despite what must have been a shocking sight to him, LeFlore drew his pistol and sabre, spurred his mount, and charged. As LeFlore approached the nearest ape, it took a mighty swipe and struck his horse in the head, killing it instantly. LeFlore managed to roll off the falling horse, quickly jumped to his feet, and fired multiple shots into the chest of the creature. Once his pistol was empty, LeFlore attacked the ape with his sabre, opening up gaping wounds on the animal which roared in rage and pain.

LeFlore’s assault on the creature was so quick, and the shock of seeing hair-covered monsters so great, that the Tubbee men hesitated, completely stupefied, before entering the fray. This delay allowed one of the other two apes to get behind LeFlore, who was intensely focused on the ape he had engaged. The second beast grabbed LeFlore’s head with two huge hands and ripped it from his shoulders. The horrible sight jolted the Tubbee warriors into action and they opened fire on the three sasquatches with 50-caliber Sharp’s buffalo rifles. Two of the beasts were killed instantly, dropping in their tracks. The third creature was wounded but turned and fled before the lethal shot could be fired. Robert Tubbee, only 18 years old but already 6’ 11” and well over 300 pounds, spurred his horse, ran down the injured ape, and dispatched him with his hunting knife.

As the rest of the troop, after gathering their panicked horses, joined them, the “Lighthorsemen” surveyed the area. The bodies of dead women and children, most partially devoured, littered the area. The smell of decay, along with the terrible odor of the beast’s feces, caused many of the men to vomit. After composing themselves, the men gathered the remains of the unfortunate women and children and buried them. They also buried their leader, Joshua LeFlore. As for the three ape-like monsters, their bodies were placed upon a huge bonfire and burned. Their hellish task complete, the Choctaw warriors returned to Tuskahoma, where it is said even the mighty Tubbee men were plagued by terrible nightmares for years afterward.

Some story, is it not? But is any of it true? While I could not find much, it does appear the Tubbees existed. So, too, did a man named Joshua LeFlore. What I could not find was any mention – at least in any official documents – that Leflore died in battle. For that matter, I have been unable to find any information leading me to believe that the LeFlore County bigfoot war took place anywhere outside of the realm of folklore.

Having said that, is it possible that the LeFlore County incident was actually based on a real event that took place in a different location? According to a bigfoot researcher named Jim King, the answer might be yes. King believes the LeFlore County story is based on an event that took place much farther west in Kiowa territory, an event related to him by an Indian elder. According to the story, Kiowa women were placed in a special teepee or tent on the edge of camp when they started their menstrual cycle. The women stayed there, being tended to only by older women, until their cycle was complete. The elder told King that women were considered “unclean” during their cycles and Kiowa warriors were not only forbidden any physical contact with the females during this time, they were not even to look upon them (This seems harsh but it not too different than the way many cultures treated menstruating women in the past.) The elder said that once, long ago, there had been trouble with ape-like creatures who were attracted by the scent and pheromones emanating from the tent where the menstruating women were housed. Since the tent was on the edge of the encampment, it proved to be an easy target for renegade apes who are said to have entered and carried off women on several occasions. To make a long story short, the Kiowa leadership decided this was unacceptable and put together a group of warriors to hunt down the kidnappers. The searchers did manage to track an ape back to its lair and killed not only it, but an entire family unit.

Could the LeFlore County story have its roots in the tale told to Jim King by the Kiowa elder? Is there any truth at all – even the smallest of grains – in either tale? I have heard many put their faith in the LeFlore County version simply due to the name of the unfortunate Joshua LeFlore. “They wouldn’t have named the county after him if it wasn’t true,” and other similar statements abound. I, however, have not been able to find anything saying LeFlore County was named after Joshua LeFlore. According to the Oklahoma Historical Society’s website, “The name honors the prominent LeFlore family of the Choctaw Nation.” Could Joshua LeFlore have been one of the “prominent LeFlore family?” It is certainly possible, but there does not seem to be any documentation singling out Joshua or his actions as the reason for the naming of the county.

The story of the LeFlore County bigfoot war, even if totally fictional, does seem to point to the fact that enormous, hair-covered, ape-like animals have been thought to reside in the region for a very long time; a time long before the Patterson-Gimlin film brought bigfoot into America’s consciousness. Add this to the beliefs of many other Native American tribes from across the North American continent who have long told stories of these creatures snatching women and children and the anecdotal evidence stack grows taller. Truth be told, the idea of child- or woman-snatching sasquatches continues to thrill, terrify, and enthrall us to this very day. One needs to look no farther than the success of David Paulide’s Missing 411 books to confirm this.

It may very well be the tale of the LeFlore County bigfoot war was inspired by actual, less dramatic events (think the siege of Honobia, the Ape Canyon incident, etc.) Over the years, such a story would be embellished and grow to mythic proportions. It is all but inevitable as a good scary story is irresistible. Do not be too hard on those who might have added to the original facts. After all, we all know the most frightening types of campfire stories will always have one thing in common…

...they could really happen.

Sources:

The LeFlore Horror/Bear [Radio series episode]. (2018, April 18). In World Bigfoot Radio #53.

Swancer, B., & Seaburn, P. (2018, June 06). The Strange Case of the Human-Bigfoot War of 1855. Retrieved August 21, 2020, from https://mysteriousuniverse.org/2018/06/the-strange-case-of-the-human-bigfoot-war-of-1855/

Nashoba, D. T. (2002, January 6). The Legend of Sacred Baby Mountain [Scholarly project]. In Google Groups. Retrieved August 20, 2020, from https://groups.google.com/g/alt.bigfoot.research/c/tD56ttwlfik?pli=1

Le Flore County: The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. (n.d.). Retrieved August 20, 2020, from https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=LE007

Frequently Asked Questions Answered

As promised, I am going to attempt to breathe some new life into the blog in 2021 so here we go. I receive a LOT of correspondence and get many questions about a variety of topics. I enjoy getting those emails and messages but I do end up answering a lot of the same questions over and over. That being the case, I thought I would make my first post of the year one in which I addressed the most frequently asked questions I get. Some of the questions are personal in nature while others are more cryptid specific.

Question: How did you become interested in cryptozoology?

Answer: I have been interested since I was a young boy. In the early 1970s, my grandmother took my brothers and me to a movie. I do not recall what the movie was that day, but I do vividly remember seeing the Patterson-Gimlin footage in a short feature before it started. I was mesmerized. It just looked real to me. I was hooked from that point forward. Television shows like In Search of… and The Six-Million Dollar Man along with movies like The Legend of Boggy Creek only solidified my interests.

Question: How many people are part of your organization?

Answer: If referring to the Texas Cryptid Hunter site, it is just me. I have had some great folks volunteer to visit sighting locations and send me photos from time to time, but there is no membership or staff.

Question: How long have you been investigating bigfoot and other cryptids?

Answer: I have been actively engaged in field work since 2005.

Question: Are you the same Mike Mayes who is Chairman of the NAWAC?

Answer: Yes.

Question: Have you ever seen a sasquatch or another type of cryptid?

Answer: Yes. I had a sighting of what I believe was a sasquatch in the Sam Houston National Forest in May of 2005. Since, I have three times caught glimpses of animals I strongly believe were wood apes in the Ouachita Mountains of southeast Oklahoma, including one just weeks ago. I have also seen one of the hairless canines news outlets have taken to calling “chupacabras” and many Texans refer to as “blue dogs.”

Question: What do you say to skeptics who deny the existence of the sasquatch or wood ape?

Answer: I find I do not worry too much about what skeptics think. I believe anyone who takes the time to seriously – and that is the key word – look into the bigfoot phenomenon with an open mind will, at the very least, come away feeling that a closer look at the topic is warranted. I fully admit that the evidence is not yet strong enough to conclusively prove these creatures exist (more on that later), but believe a properly funded entity (National Geographic Society, major university, etc.) could obtain concrete evidence if willing to commit the proper resources and time.

Question: Many scientists deny the existence of bigfoot because they have spent many years in the field and have never seen one. How is it that they have never had a sighting?

Answer: How did the okapi stay hidden so long? The truth is that practically no one is looking for the sasquatch. Even field biologists spend most of their time in labs or at universities. The actual amount of time in the field for most is usually pretty limited and they tend to be funded by grants that dictate the specific research they are to be conducting. There is no time or money for “bigfoot hunting.” I would add the majority of witnesses state something along the lines of "I've hunted for X years and never seen anything like that" or "I've lived here my whole life and have never seen anything unusual." These animals are extremely furtive and these sorts of statements are the norm rather than the exception. Most people who spend time in the woods won't see them.

Question: With all the trail and surveillance cameras out there, why are there no photos of wood apes?

Answer: Most trail cameras are placed by hunters watching feeders and/or food plots. Even these cameras are rarely left up year round. There are often regulations that limit how long cameras are allowed to be left up on public land. Too, these cameras are rarely deep into the wilderness where I believe these animals spend most of their time. A hunter typically places his cameras no more than 100-300 yards off a road or an ATV trail. As for surveillance cameras, there are not many of them out in the middle of the forest. Having said that, there are at least a few extremely compelling images and videos that have been captured. The fact that they have garnered so little attention from the scientific community proves that no photo or video will ever be enough to get this species officially documented.

Question: Why have we not found the body/bones of a sasquatch?

Answer: Nature simply does not allow a body to last very long. In a true wilderness, environmental factors like temperature, humidity, insects, scavengers, and acidic soils work to “clean up” a body very quickly. Think about how often the body of a bear or mountain lion – two species that are almost certainly more prolific than wood apes – that died of natural causes are found in the woods. The answer, of course, is almost never. Consider, too, that many animals often seek the most remote and inaccessible location possible when they are sick or injured (think about a sick dog that hides under the porch of a house). Should an animal die in one of these locations, the chances of a human hiker or hunter finding it are pretty small. I do feel it is possible bones have been found and were misidentified and left behind due to their not being thought of as anything special. Outside of a skull or pelvis, most bones are not easily identifiable to laymen.

Question: Do you believe it is necessary to collect a specimen in order to prove the species exists?

Answer: Yes, I do. It may be unsavory to many – and I understand that – but science requires a body. It really is that simple. A compelling photograph or an anomalous DNA sample might get the attention of some in the scientific community, but for the species to be officially recognized, it will take a specimen. That is just the way science works.

Question: If bigfoot is an endangered species, won’t collecting a specimen increase the odds of of it going extinct?

Answer: No, I do not believe that. The collection of one individual should have no effect on the entire population of animals. The key here is to think in terms of a population as opposed to thinking of an individual. Collecting one – and one is all I would approve of - in order to save the population is worthwhile. The government will never set aside preserves or sanctuaries or legally protect the wood ape until it moves from the realm of myth and cable television into the pantheon of known and documented creatures. If the collection of one specimen is enough to send the species spiraling into the abyss of extinction, the animal is functionally extinct already.

Question: Why don’t you just try to tranquilize a specimen and capture it instead?

Answer: The short answer is that such an undertaking is immensely complicated, expensive, and dangerous. Tranquilizing an animal – especially one as large as most wood apes are reputed to be – is an extremely dicey undertaking. I think it would be all but impossible. For more on this topic, listen to the latest episode of the NAWAC’s official podcast, The Apes Among Us, titled “Exploring Alternative Paths to Discovery.”

As you can see, most of the questions I get are in regard to the bigfoot phenomenon. The sasquatch remains the undisputed “king of the cryptids” when it comes to public interest. For more answers to the most commonly asked wood ape questions, see my Sasquatch FAQ Series.

Check back soon as I have several other posts in the works including new black panther reports, historical bigfoot sightings, and an update on the NAWAC’s “Hadrian’s Wall” camera project.

The Missionary, the Former Slave, and the Sasquatch

What do an eighteenth-century Jesuit missionary and a former slave from the state of Arkansas have in common? I hate to disappoint any of you that thought this might be the line to a bad joke, it is actually a legitimate question. Read on for the answer.

In my mind, some of the strongest sources of anecdotal evidence regarding the existence of the sasquatch are those that pre-date the coining of the term bigfoot in an article about a catskinner named Jerry Crew - who found massive human-like tracks around his road-building equipment in California’s Six Rivers National Forest in August of 1958 - and the explosion of the Patterson-Gimlin footage on the world stage in October of 1967. Sightings reported before these two seminal events cannot be dismissed as the work of hoaxers seeking to hop on the bigfoot bandwagon. The sasquatch was all but unknown to the Europeans who began flooding the North and South American continents in the 1500s…and to the slaves that they brought with them. Their accounts of bipedal, hair-covered creatures simply cannot be dismissed out of hand.

I would like to discuss here two such historical sightings. The incidents are not well-known, but they may well be extremely important when attempting to trace just how far back sightings of wood apes might go. The similarity between these two accounts cannot be denied and both lend credibility to the opinion of those who believe the animal commonly referred to as bigfoot was being seen well before the 1950s by people of different cultural backgrounds living many miles apart.

The first incident comes directly from the writings of a Jesuit missionary who worked among the people of the province of Sonora, Mexico – a region that stretched up from northwest Mexico to the Sierra Madre from Cjeme (now Ciudad Obregon), near the California coast, to Tuscon - in the eighteenth-century. Father Ignaz Pfefferkorn (b. 1725), a German Jesuit lived and worked among the Pima Indians from 1756 to 1767. Details of his work and life among these people can be found in his Descripcion de la Provincia de Sonora. The diaries, journals, and logs of missionaries have long been highly valued by anthropologists and historians. Pfefferkorn’s work was no different and he is considered by academics to have been an extremely reliable and credible observer. His writings continue to be cited by historians to this day. Among Pfefferkorn’s writings were descriptions of the local wildlife. Among the descriptions of what would be considered common animals, the good father wrote about the different bears (differentiated by their color) found in the region. He wrote:

“Of the Sonora bears some have black hair, others dark gray, and the smallest number are a reddish color. These last are the most cruel and harmful, according to the statements of herdsmen.”

Only two species of bear are known to have ever lived in the Province of Sonora during the eighteenth-century. The black bear (Ursus americanus) and the grizzly (Ursus arctos horribilis) both made Sonora part of their home range during the time in question. While black bears can be black, blonde, or reddish, it is likely the cinnamon-colored bears that were “the most cruel and harmful” were grizzlies. While these grizzlies were likely the animals most often responsible for the killing of livestock in the region, some of the other activities attributed to them may well have been the work of something else.

Pfefferkorn, while documenting bear activity related to him by the indigenous tribesmen, in some cases may have actually been recording accounts of bigfoot interaction with humans. If so, his accounts are some of the earliest ever written down in North America. One intriguing passage is below:

“Bears are a special menace to stock raising, for they eat many a calf, and, if no smaller prey falls into their clutches, they will attack even horses, cows, and oxen. They delight especially in eating maize as long as it is still tender and soft. Woe to the field if a hungry bear breaks into it at night. He eats as much as he can and makes off with as much as he can grasp and carry in his mighty arms. In so doing he ruins even more of the field by breaking it down and treading upon it. The inhabitants assert that a bear defends himself by throwing stones when one attempts to chase him away and that a stone hurled from his paws comes with much greater force than one thrown from the hand of the strongest man.”

I do not think I have to tell anyone that a bear cannot throw stones; nor is it capable of walking bipedally in order to carry off large amounts of corn in its “mighty arms.” Pfefferkorn was familiar with bears. He had traveled across the region for many years and had seen many bruins. Pfefferkorn even witnessed a grizzly kill his Indian guide on one trip across Sonora (the guide had attempted to kill the bear, succeeded only in wounding it, and paid the ultimate price when the animal turned on its tormentor). This being the case, it is strange that Pfefferkorn would attribute rock-throwing and the ability to carry large amounts of corn away while walking on two legs to grizzlies. I think it is entirely possible that the stone-hurling, corn-stealing, bipedal “bears” of Sonora might have actually been wood apes.

A strikingly similar account comes from another historical source: a former Arkansas slave. Doc Quinn was one of the oldest living residents of Miller County, Arkansas (yes, the same Miller County that would become known as the home of the Fouke Monster of The Legend of Boggy Creek fame) when he was interviewed by Cecil Copeland at his home in Texarkana in the 1930s. Doc recalled when he was first brought to the plantation of one Colonel Ogburn – between Index and Fulton on the Red River - that there was a section of the property dominated by an immense canebrake. This canebrake was a favorite retreat of bears and other wild animals. It was all but impossible to go in after problem bears that would steal out of the thicket at night and take livestock, so the plantation owner had the slaves round up the hogs and animals and place them in pens at the end of the day. Several slaves were charged with standing guard at night over the domesticated animals. The efforts of the slaves helped somewhat, but bears were still seen often and some of their actions “were almost human.” The following is a passage taken from the book Bearing Witness: Memories of Arkansas Slavery Narratives from the 1930s WPA Collection in which Doc Quinn describes to Cecil Copeland the odd behavior of a “bear” he came across in a cornfield one day:

“The bear picked off an ear of corn and put it in his bended arm. He repeated this action until he had an armful, and then waddled over to the fence. Standing by the fence, he carefully threw the corn on the other side, ear by ear. The bear then climbed the fence, much in the same manner of a human being, retrieved the corn, and went on his way.”

Sounds familiar, does it not? The simple truth is that bears cannot stroll around in a bipedal fashion while plucking ears of corn from stalks in the field with one front paw and place them into the crook of their other front “arm.” The description of how Quinn witnessed this animal climb a fence “in the same manner of a human being” is fascinating. The entire incident simply does not describe bear behavior in any form or fashion.

Quinn provides another interesting anecdote in the same interview. I thought long and hard about including it here, not because it is not interesting (it is), but because Doc Quinn’s words are transcribed in such a way that his dialect is evident. Some hot-button words, including the n-word, are used. After wrestling with it for a while, I decided to include the account here with only one minor edit (I decided not to type the n-word out. I fear in today’s climate, I would be accused of approving of it or some such thing). Again, I would remind readers these are not my words. These are the words spoken by former Arkansas slave, Doc Quinn and transcribed by his interviewer, Cecil Copeland. The text comes straight from the book previously mentioned. Try to focus on the story Doc Quinn is telling and not the language and terminology he uses. The account is as follows:

“Late one ebenin’, me an’ anudder (edit) named Jerry wuz comin’ home frum fishin’. Roundin’ a bend in de trail, whut do we meet almos’ face to face? – A great big ol’ bar! Bein’ young, and blessed wid swif’ feet, I makes fo’ de nearest tree, and hastily scrambles to safety. Not so wid mah fat frien’. Peerin’ outen thru de branches ob de tree, I sees de bar makin’ fo’ Jerry, an’ I says to mahself: ‘ Jerry, yo’ sins has sho’ kotched up wid yo’ dis time.’ But Jerry, allus bein’ a mean (edit), mus’ hab had de debbil by he side. Pullin’ outen his Bowie knife, dat (edit) jumps to one side as de bar kum chargin’ pas’, and’ stab it in de side, near de shoulder. As de bar started toinin’ roun’ to make annuder lunge at de (edit) he notice de blood spurtin’ frum de shoulder. An’ whut do yo’ think happen’? Dat ole bar forgets all about Jerry. Hastily scramblin’ aroun’, he begins to pick up leaves, an trash an’ clamps dem on de wound, tryin’ to keep frum bleedin’ to deaf. Yo’ ax did de bar die? Well, suh, I didn’ wait to see de result. Jerry, he done lef’ dem parts, an’ not wantin’ to stay up in dat tree alnight by mahself, I scrambles down an’ run fo’ mile home in double quick time!”

I ask you, what kind of bear notices it is bleeding, stops in the middle of an altercation, begins gathering leaves, and then packs its own wound? I will tell you the answer. None. No bear behaves in this manner. If Doc Quinn is not spinning a yarn to his interviewer, the creature his fishing partner, Jerry, tangled with was certainly no bear. Was it an aggressive sasquatch? Certainly, the location was right as the aggressive nature of the Fouke Monster would be well documented some years later. There is a real shortage of viable alternatives if the creature in question was not a bear.

The parallels between these two accounts – accounts separated by more than a century and approximately 1,400 miles – are uncanny. Bears cannot and do not gather up corn in their “arms” and walk away with it in a bipedal fashion. Yet, a Jesuit missionary and a former Arkansas slave describe observing this same behavior. Doc Quinn’s account of how his fishing partner, Jerry, tangled with an animal that packed its own wound after being stabbed lends credence to the theory that something other than a bear was roaming about Miller County, Arkansas in his youth. Is it possible that these two men from very different worlds - Father Ignaz Pfefferkorn and former slave Doc Quinn - described the same type of animal? An animal they had no name for? An animal that just might have been a wood ape?

Food for thought.

*Special thanks to NAWAC Chairman Emeritus, Alton Higgins, who authored the article, “A Sonoran Sasquatch,” that I drew heavily from for this post.

Sources:

Brown, D. E. (1996). The Grizzly in the Southwest: Documentary of an Extinction. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

Pfefferkorn, I., Treutlein, T. E., & Pfefferkorn, I. (1949). Sonora A Description of the Province. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Higgins, A. (2010, November 19). A Sonoran Sasquatch? Retrieved January 11, 2021, from https://www.woodape.org/index.php/sonoransasquatch/

Lankford, G. E. (Ed.). (2006). Bearing Witness Memories of Arkansas Slavery. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press.

Once in a Lifetime: Steller's Sea Eagle Spotted in Texas

Most of us would consider our chances of winning the lottery or being struck by lightning as highly unlikely. The odds of such an event occurring in the life of an individual are ridiculously long. Another event that would carry similar long-shot odds would be spotting a Steller’s sea eagle in south Texas; yet, it appears that event has actually taken place.

The fun started on March 10th when a photo of a Steller’s sea eagle was posted on the Facebook page of the Barnhart Q5 Ranch & Nature Retreat. According to the post, the bird was spotted on the Coleto Creek arm of Coleto Creek Reservoir and downstream from the Coletoville Road bridge in Goliad County. The snag on which the eagle was perched has been found and the location verified according to my contacts in the birding community. Those same contacts have told me there is no sign of photoshopping or other doctoring of the original image. More and more of the Texas birding community – who initially scoffed at the possibility of this species being seen in the Lone Star State – are coming around to the likelihood that the sighting is legitimate.

If true, how could a Steller’s sea eagle have gotten so lost? The first possibility is that it did not. Some have speculated that what was seen was a bird that escaped from a zoo or a falconer. It is a theory that would neatly sum up the mystery as to how this eagle ended up at least 5,000 miles from home; however, there are problems with this hypothesis. There are very few Steller’s sea eagles in U.S. collections. According to several veteran Texas birders to whom I spoke, there are less than 20 of these eagles in captivity in the United States. A quick search revealed that zoos in San Diego, Cincinnati, Denver, Boise, Louisville, and New England house specimens. These are some of the heavyweights of the zoo world in North America and not roadside menageries with a ramshackle enclosures that might make escape possible. None of these zoos have reported a missing eagle. These same birders went on to address the falconer theory and said this explanation is unlikely. One said, “It would be an extremely tough bird for a falconer to even obtain.” To sum up, the idea that this bird is an escapee has lost a lot of steam.

Another possibility as to how this eagle found its way to Texas is that there is something wrong with it. Occasionally, individual birds lose their ability to navigate properly. It is almost as if their internal compass suddenly ceases to operate correctly. This loss of navigational ability has led to sightings of species far outside of their normal ranges. One such recent example is the case of a great black hawk (Buteogallus urubitinga) – a bird that is native to South America, Central America, and Mexico – that ended up in Maine in 2019. This incident ended on a sad note when the hawk was found near frozen one cold January day. The bird was taken to a rehabilitation center but suffered frostbite on its feet and had to be euthanized. The only explanation for how this species managed to get 2,000 miles from its accepted home range is that something in its internal navigation system went haywire. We can only hope that a happier fate awaits the Texas Steller’s sea eagle.

So, if you are in the Goliad area, you might want to take a ride out to Coleto Creek Reservoir and see if you can catch a glimpse of this magnificent, wayward eagle. While you are out, you might want to buy a lottery ticket as well. As this Steller’s sea eagle has proven, sometimes long-shots pay off.

Sources:

Steller's sea eagle. (2021, March 02). Retrieved March 16, 2021, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steller%27s_sea_eagle

Facebook. (n.d.). Retrieved March 16, 2021, from https://www.facebook.com/BQ5RANCH/photos/a.2097168407009460/4136167156442898/

Great black hawk. (2021, March 15). Retrieved March 16, 2021, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_black_hawk

Maine's great Black Hawk - rescued! (2019, January 31). Retrieved March 16, 2021, from http://www.10000birds.com/maines-great-black-hawk-rescued.htm

The Legend of the Belled Buzzard

Going on ten years ago, I was out checking on some game cameras here in Central Texas. I had placed my cameras along the Lampasas River below the Stillhouse Hollow Dam. My cameras never captured anything unusual while in this location, but I did experience something a bit odd one day while servicing them. I was changing out batteries on one of the cameras when I thought I heard the tinkling of a bell. It was a sound akin to that made by a small, round “sleigh bell.” I turned to look around, but saw nothing. I started to get on with the task at hand when I heard the bell again. This time, the sound seemed to emanate from somewhere above me. I looked up into the trees but saw only a few black vultures (Coragyps atratus) lingering about. The whole thing was a bit odd, but – and you know this if you have followed the blog for any length of time – I have had much stranger experiences while out in the woods so I just finished the chore of refreshing my trail camera. I did not hear the sound again that day, or on any of my subsequent trips to the location, and thought so little of it I did not mention it in the blog post I made later regarding the photos I had captured on that particular set. I had not thought about that day in years, but a recent discovery brought it all back and made me wonder about what I might have heard that day.

Recently, I was thumbing through a book called Unexplained! By Jerome Clark at the Temple Public Library. I was flipping through the usual chapters on the UFOs, sasquatches, yetis, and Loch Ness monsters of the world when my eyes fell upon an entry titled “Belled Buzzard.” Never having heard of such a thing, I began reading. Imagine my surprise to find out that many odd stories have been published over the years – most between 1860 and 1950 – about a “belled buzzard.” Reports spanned the continent from the Dakotas to Florida, but a couple of locales popped up more than any others: Indiana and, you guessed it, Texas.

The origin of the belled buzzard legend is hazy at best. The earliest sightings seem to have occurred in 1869 in Tennessee. These encounters were documented in the Memphis Appeal in the early summer months of that year and the stories were picked up and reprinted by other newspapers across the country. The term belled buzzard is not used in the articles, but related were the tales of two separate accounts where multiple people spotted a buzzard (a colloquial term for a vulture) with a small bell around its neck. The sightings took place on a farm near Burnsville and witnesses described the bird seen as seeming “more than usually wild.”

Following are snippets of the earliest Texas accounts I could locate:

Pilot Point, April 25, 1893. “The belled buzzard was seen…by Mrs. Keys and family on their farm near town and as usual it was not accompanied by any of its kind” (Dallas Morning News, April 30)

Erath County, March 18, 1894. “Col. J. L. Hansel…always doubted reports concerning the famous ‘belled buzzard.’ He did not believe until yesterday afternoon that such a buzzard existed. He was out in his yard when above him he heard a bell ringing. Looking up he saw a buzzard with a bell hanging on its neck” (Dallas Morning News, March 20).

Nunn, early June, 1894. “M. K. Ownsly and Will James caught a belled buzzard… The bell was branded ‘J’ and was attached to the buzzard’s neck by a leather collar” (Dallas Morning News, June 15)

Longview, June 27, 1894. “A buzzard wearing a sheep bell was seen by several citizens yesterday morning. The belled buzzard has been seen at numerous places in this state…Mr. O. H. Methvin and his son, over whose corn field he circled several times, thought it was a belled sheep or calf in their corn and tried some time to find it” (Dallas Morning News, June 29).

Chatfield, April 3, 1898. “’The belled buzzard’ has been captured. It was caught…last Sunday. The bell consisted of an oyster can securely tied about the bird’s neck with a ten-penny nail as the bell clapper. It was trapped on the farm of Mr. T. B. Roberts, liberated from the burden, which had cut into the flesh, and the bird turned loose. The can is on exhibition at Shook’s drug store” (Dallas Morning News, April 10, quoting the Corsicana Chronicle, Texas).

Woodbury, October 29, 1900. “J. C. Goldfrey…informed The News correspondent that the celebrated belled buzzard spent the day on his farm yesterday. He saw it several times and distinctly heard the bell which he described as having a tin sound” (Dallas Morning News, October 31).

Falfurrias, early February, 1931. “A belled buzzard may be seen daily in the Flowella section…Mrs. J. F. Dawson and her son, Jimmie, were working in the yard…when suddenly they heard the tinkle of a small bell, seemingly out of the blue sky. After straining their eyes in every direction for a short time, they discovered his buzzardship lazily floating along, while with each flap of his wings the little bell tinkled” (San Antonio Express, February 15).

Just where did this belled bird or birds - for surely it had to have been more than one vulture responsible for the plethora of sightings - come from? One of the origin stories that seems the most credible came from physician C. A. Tindall of Shelbyville, Indiana. While being interviewed by an International News Service Reporter in March of 1930, the good doctor – after discussing a recent sighting – said, “It calls to mind an incident that occurred about 1879 or 1880 on the old home farm four miles out of Shelbyville.” Dr. Tindall goes on to say that he and his brothers discovered a buzzard’s nest on the family property and were able to catch a hen guarding her eggs. “We put a sheep bell with a leather strap around the body of the buzzard,” he said. “In front of one wing and behind the other. As the buzzard soared away the bell tinkled.”

The other story of the how the belled buzzard got its start caught my eye as it originates from Belton, Texas. (I teach school in the Belton ISD.) In a 1968 interview with the Belton Journal, eighty-year-old Irma Sanford Eddleman was coerced by her daughter to tell a unique story from her childhood. One day (the specific year is not mentioned), a young Irma and her little brother noticed several vultures circling the carcass of a recently deceased chicken that had been disposed of behind their house. “My little brother and I decided to catch one,” Irma said. “I did. It jerked me almost two feet off the ground, trying to get away, and how it stank. But I held on, and sent my brother into the barn to get a length of wire that had a bell on it. We wrapped the wire around that bird’s neck, and let it go. My father worried for days about a bell ringing up in the air; he could hear it in the early morning up in the sky. My brother and I did not say a word.” Ms. Eddleman went on to express regret for the prank. “I’m not at all proud of that,” she said. “It was the unthinking act of a child, and not a kind one.”

While the origin story of the belled buzzard may be hazy, what can be said for sure is that for the better part of four decades sightings of the unfortunate vulture were reported in newspapers on a semi-regular basis. After that, newspaper stories regarding the famous belled buzzard became increasingly rare, though they never went away completely.

As might be expected, the belled buzzard achieved something akin to mythical status among rural Americans living through the heyday of sightings. To some, the appearance of this belled vulture was a harbinger of misfortune or even death. In other places, however, the sighting of the belled buzzard was anything but a bad omen. To some, the appearance of the famous bird over a rural homestead was “regarded as an infallible sign that there was to be an addition to the family. Mothers instead of telling their children of the stork’s visit informed them that the belled buzzard was the bearer of the little one” (Philadelphia Record, 1908). The legend became so well-known that a story, written by Irvin S. Cobb, about it was published in the Saturday Evening Post in 1912.

Like today, skeptics abounded during the belled buzzard craze. Witnesses were often ridiculed and public questioning regarding their state of mental health and drinking habits were standard. The possible existence of such a bird was deemed too ridiculous to take seriously and, therefore, had to be figments of fevered/drunken imaginations or outright fabrications. Clark writes in his book, “In 1897, when mystery airships (a late nineteenth-century equivalent to modern UFOs) were reported in various parts of the country, witnesses received the same treatment. In fact, mystery airships and belled buzzards were sometimes mentioned in the same humorous or unflattering sentences.”

As a native Texan, I can tell you that there is no tradition of belling buzzards – nor any other type of bird – here. Neither has it ever been a common practice across the American South or Midwest. I find it plausible – as the previously mentioned origin stories relate - that someone somewhere caught and attached a bell to either a black or turkey vulture at some point as a prank, inadvertently birthing a legend. No doubt, there were some copycats who duplicated the stunt. (It is the only way so many birds could have been seen across such a vast amount of the continent over so many years.) For whatever reason, sightings of belled buzzards are all but non-existent now, but in their day the existence of these mysterious vultures was as hotly debated and controversial as the possible existence of the sasquatch or UFOs are today.

As I close, my mind once again drifts back to that day along the Lampasas River a decade ago. I heard what I heard and numerous vultures were present. Is it possible the belled buzzard – who may have gotten his start in nearby Belton – had returned home after all these years? Surely, not.

Right?

Sources:

Clark, Jerome. Unexplained! Third ed., VISIBLE INK PR., 2012.

Cobb, Irvin S. “The Belled Buzzard.” The Saturday Evening Post, 28 Sept. 1912.

“Indiana University Bloomington.” ""Belled Buzzard" from Library", http://webapp1.dlib.indiana.edu/images/item.htm?id=http%3A%2F%2Fpurl.dlib.indiana.edu%2Fiudl%2Flilly%2Fhohenberger%2FHoh006.091.0016.

Lindaseccaspina, and Lindaseccaspina. “Don't Fear the Cow Bell - the Belled Vulture.” Lindaseccaspina, 31 May 2021, https://lindaseccaspina.wordpress.com/2021/05/31/dont-fear-the-cow-bell-the-belled-vulture/.

Sasquatch Classics: Daniel Boone and the Yahoo

Daniel Boone was born on November 2, 1734 near the present-day town of Reading, Pennsylvania. The sixth of eleven children born to Squire Boone and the former Sarah Morgan, he would go on to earn great fame as a hunter, soldier, politician, statesman, woodsman, and guide. To this day, his is a household name that inspires images of trailblazing adventure and life on a frontier now long gone. Volumes have been written on this legendary figure’s life and of late, I have read through several tomes about this American legend. While doing so, one incident related by the great man himself kept popping up that seems to have been given short-shrift by each his biographers: Boone’s claim that he once shot and killed a ten-foot tall, hair-covered beast, called a “yeahoa” or “yahoo,” in the region that would one day become Kentucky or West Virginia.

It is easy to see why a biographer of Boone would not know what to think about such a claim. The man did not suffer fools gladly, nor did he tolerate being thought of as one. This is obvious to anyone who reads about how Boone handled being dragged through a humiliating court-martial in 1778. Though he was found not guilty - and was even given a promotion in rank after the court heard his testimony about the matter in question – the frontiersman remained bitter about the entire affair and rarely spoke of it. The grudge against his accusers is one Boone held until the day he died. Yes, Boone was very conscious of his reputation and public image. That being the case, it seems odd he would make a claim as bizarre as having killed a monster.

Some biographers go into more detail than others about the alleged incident; however, all seem to agree on the basic details of how the story came to light. Late in his life, Boone was holding court with a group of distinguished citizens at a dinner held in his honor at an inn in Missouri. At the conclusion of the meal, a question-and-answer session of sorts seems to have taken place. It was at this time that one of the men in attendance asked for a story. It is unclear if the gentleman asked for the particular yarn he ended up hearing or if Boone decided on the tale to be told. Either way, the story Boone shared was one of having come upon and shooting a ten-foot tall, hair-covered “yahoo” in the Appalachian wilderness many years before. The old frontiersman did not get too deep into the tale before one of the men listening laughed out loud and declared the story “impossible.” Accounts indicate that Boone was deeply offended and refused to continue despite the requests of the others in attendance. The awkwardness of the situation led to the premature end of the get-together and people began making their exits. After most of the others had left, the innkeeper’s son petitioned Boone to finish.

“I would not have opened my lips had that man remained,” said Boone.

“Well, we are alone now,” the boy replied.

The frontiersman is said to have smiled wryly before saying, “You shall have it…” and finishing the story for the lad and the few holdouts who quietly made their way back into the room once it was obvious the story-telling had recommenced.

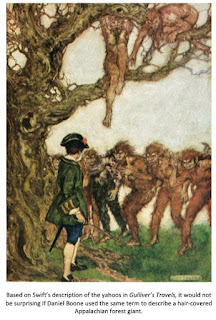

While Boone never received much in the way of formal schooling – and his spelling was notoriously “creative” – he read well. His early favorites were history books. It is also said Boone took a strong liking to Robinson Crusoe. Later, two books dominated the frontiersman’s reading time: the Bible and Gulliver’s Travels. Written by Irish writer and clergyman, Jonathan Swift, Gulliver’s Travels became an instant hit upon publication in 1726. Most likely think they are familiar with the plot of Gulliver’s Travels in which the main character finds himself shipwrecked on the shores of an island nation called Lilliput and is taken prisoner by a horde of the island’s tiny inhabitants. It is true this is the most well-known part of Swift’s masterpiece; however, the tale of Lemuel Gulliver’s trials and tribulations among the Lilliputians is just part of the overall work. It is actually the story of Gulliver’s fourth voyage that concerns us in regards to the tale told by Daniel Boone.

In Part 4 of the book, titled “A Voyage to the Country of the Houyhnhnms,” Gulliver – who has tired of his life as a surgeon – returns to the sea as captain of a merchant vessel. After several crew members die, Gulliver hires replacements out of Barbados and the Leeward Islands. Unfortunately, the new hires turn out to be buccaneers and soon mutiny. The pirates strand Gulliver on the first piece of land they come across and sail away in his ship. It is now that the story becomes relevant to the Boone tale as the fictional Gulliver soon encounters some terrifying creatures:

“At last I beheld several animals in a field, and one or two and deformed, which a little discomposed me, so that I lay down behind a thicket to observe them better…their heads and breasts were covered with thick hair, some frizzled and others lank; they had beards like goats, and a long ridge of hair down their backs…they often stood on their hind feet…”

Another passage reads:

“My horror and astonishment are not to be described, when I observed in this abominable animal, a perfect human figure: the face of it indeed was flat and broad, the nose depressed, the lips large, and the mouth wide…the forefeet (arms) of the Yahoo differed from my hands in nothing else but the length of the nails, the coarseness and browness (sic) of the palms, and the hairiness of the backs. There was the same resemblance between our feet, with the same differences…the same in every part of our bodies except as to the hairiness and colour (sic)…I never saw any sensitive being so detestable on all accounts; and the more I came near them the more hateful they grew…”

Daniel Boone was intimately familiar with the yahoos described in Gulliver’s Travels. If he had ever come into contact with a huge, hair-covered, human-like beast in his years of traversing the American wilderness, calling the beast a yahoo – based on the description of the creatures written by Swift – seems natural enough. To this day, the names Yeahoh and Yahoo are used to describe sasquatch-like creatures said to roam the mountains and forests of Appalachia.

Critics say Boone’s tale of shooting a bigfoot-like creature is just a campfire story meant to entertain his rapt followers who hung on his every word. Boone biographer, Robert Morgan, would seem to concur and wrote, “He (Boone) was also known to tell tales about encountering great hairy monsters like the yahoos in Gulliver’s Travels. Most likely it never happened.” It is hard to blame Morgan for having doubts about such a fantastic claim, but he dismisses the tale without any elaboration. While the story might be hard to take at face value, Morgan himself writes about the integrity of Boone and how much he valued his reputation. It would seem proper for the author to explain why the famous woodsman would veer from his character and fabricate a story about having killed a monster, especially when it seems all scholars agree regarding how offended the frontiersman became when his story was challenged.

Boone is said to have related the tale of the yahoo on multiple occasions, most often during the last year of his life. Some have speculated that he might have been losing his faculties during his 85th and final year on this earth. Others correctly point out that the “deathbed confession” is a real phenomenon. People confess all manner of things when they realize the end of life is near. Such confessions are thought to help alleviate feelings of guilt or regret the dying person may have been harboring during their lifetime. Too, the “deathbed declaration” - when a dying person shares some secret knowledge - is not an unusual occurrence. Usually, these declarations have to do with feelings the dying individual has for another person; however, sometimes knowledge is shared which the person has been holding onto for years, decades even. Such dying declarations have sometimes been used in court as evidence; indeed, at times, the final words of a dying man/woman are given more credence in such a scenario, as common sense would seem to indicate that they no longer have anything to lose or gain by sharing what they know.

It is true Boone told the story of the yahoo multiple times over his final year(s), but not on his literal deathbed. Still, Boone’s health was beginning to wane and any man once he reached the age of 85 would realize that there was precious little time ahead of him. Too, men of a certain age often get to a point where they could not care less about what others think of them and no longer concern themselves with how they might be ridiculed. Could the knowledge that his time on earth was short have motivated Boone to relate his incredible tale while he still could? Was it important for him to share the story – one he had kept to himself for years – before leaving this mortal plane? Perhaps.

It is highly doubtful that the truth about whether or not Daniel Boone shot and killed a sasquatch-like creature will ever be known. What is inarguable is that Boone spent more time in the American wilderness than just about any white man who has ever lived. That being the case, if the sasquatch is a real creature, who would have been more likely to eventually come across one than Daniel Boone?

Sources:

Faragher, John Mack. Daniel Boone: The Life and Legend of an American Pioneer. The Easton Press, 1995.

Morgan, Robert. Boone a Biography. Recorded Books, 2008.

Mart, T. S. The Legend of Bigfoot: Leaving His Mark on the World. Indiana University Press, 2020.

Swift, Jonathan, and David Womersley. Gulliver's Travels. Cambridge Univ. Press, 2012.

“Daniel Boones' Sasquatch.” Daniel Boones' Sasquatch Story, enigmose.com/daniel-boone-sasquatch.html.

Peacock, Lee. “Did Pioneer Daniel Boone Really Kill a Bigfoot-like Creature Prior to 1820?” Did Pioneer Daniel Boone Really Kill a Bigfoot-like Creature Prior to 1820?, 1 Jan. 1970, leepeacock2010.blogspot.com/2017/05/did-pioneer-daniel-boone-really-kill.html.

Book Announcement

It has been too long since I posted here on the blog; however, I am happy to say that I have not been idle during my time away. For the last year, or so, I have been trying to finish up my latest book project. It has pretty well eaten up all of my “free” time but I am happy to say that the book is now complete and mere days away from being available to the public.

Valley of the Apes: The Search for Sasquatch in Area X chronicles my time in the North American Wood Ape Conservancy, the evolution of the group from its old TBRC days, the difficulties inherent to hunting the most elusive animal on the North American continent, and the amazing events/encounters experienced by NAWAC members in the eerily named Area X and other locations over the last decade.

I truly enjoyed reliving the many incredible events documented in the book – many of which I had not thought about in years - and hope that, even in a small way, my efforts help in legitimizing the efforts to document this most amazing creature. Perhaps a primatologist, wild life biologist, or famous naturalist – should any deem the book worthy of reading – will see similarities between the wood ape behaviors documented and the behaviors of the known great apes. If so, maybe it will give them pause and cause them to consider the possibility that the existence of the sasquatch is not so outlandish after all. If my efforts help remove even a small part of the stigma associated with seriously researching this topic, then I will consider the book a success.

A guy can hope, right?

*Check here on the blog, the Texas Cryptid Hunter Facebook and Twitter pages, and my personal author's page (michaelcmayes.com) for updates on when Valley of the Apes: The Search for Sasquatch in Area X is available for purchase.

Historical Jaguar Sightings in Texas

My wife’s birthday was this week. She did not want a traditional gift; instead, she wanted to start redecorating our home (I blame Chip and Joanna of Fixer Upper and Ben and Erin of Hometown for infecting her with this renovation fever). I realized that this was going to cost me a lot more than a pair of earrings and an Olive Garden dinner but I love my wife and, begrudgingly, had to admit that a bit of “modernizing” was probably in order. The work started today with the arrival of a crew who were charged with painting the kitchen, dining room, bedrooms, and living room. I, of course, said that there was no need to hire painters as I could do the work myself. My lovely wife replied, “Honey, I don’t want you to spend your summer off working on the house. Why don’t you go get some writing done at the library?” Translated, this means, “I don’t want this job to cost twice as much as it should have after you mess it up and we have to hire these guys anyway. Now, make yourself scarce.”

Though deeply wounded (not really, but still…), I was glad to have blundered into a free afternoon and did, indeed, make my way to the Townsend Memorial Library on the campus of the University of Mary Hardin-Baylor. While not a large library, Townsend does have a robust folklore section and I am nowhere close to having gone through it all. As I sat down with a copy of From Hell to Breakfast, a collection of old Texas tales published in 1944, I came across a chapter titled “Panther Yarns.” Intrigued, I dug in and started reading. For the most part, I did not come across anything I was not already familiar with in regard to historical Texas panther sightings. I did some pretty exhaustive digging into this topic while researching my book Shadow Cats: The Black Panthers of North America several years ago. Still, I read on hoping to come across something new. Luck was with me as I came across two accounts with which I was not familiar. While not true black panther accounts, the two news articles do document the killing of two very large spotted cats that I suspect were jaguars (one of the suspects in the black panther mystery since they carry the genetics for melanism).

The first tale comes from an 1854 newspaper account detailing an encounter with a “Mexican Lion,” one of the terms Texans in the 1800s used to describe jaguars (“Mexican Tiger” or “Mexican Tigre” were also used periodically). Following is an excerpt from the article:

MEXICAN LION - We wish to inform you of a varmint of awful size, that was taken in camps, or killed, as I should say, at the above named place (Hays County), on the night of the 15th. It came down in the settlements of Blackwell’s Valley, and surprised the natives by taking a two-year-old hog out of the pen, (fat at that) and carrying it off. Its pursuers were Mrs. Stockman, Mrs. Thomas, and Miss Winters, who, with the aid of some dogs, caused it to take a tree; after which Mrs. Stockman procured a gun, and made an attempt to shoot it. When in the act of firing, the Mexican Lion - for this is the name of the animal – made a spring at her; she dropped the gun without firing, just in time to save herself from his claws…Mr. J.H. Blackwell, with his dogs, came to their aid, and made it take a tree again. When just in the act of shooting, it made a second attempt to spring on its assailants, but Mr. B., more fortunate than Mrs. S., fired and brought the monster to the ground, dead. It measured nine feet in length, three and a half in height, and weighed 220 pounds. Its claws were two inches in length, and its teeth about the same. The skin, claws, and teeth of the animal can at any time be seen at my residence, on the Blanco, fifteen miles above San Marcos.

G.W. Blackwell

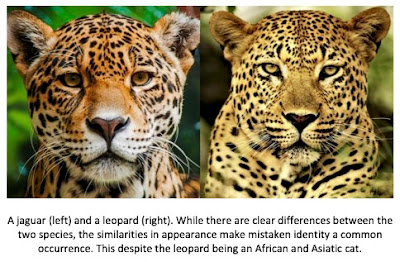

The second article comes from a story printed in the Telegraph and Texas Register on December 31, 1840. The article describes a “leopard.” I strongly suspect what was seen was actually a jaguar. Following is an excerpt from this article:

Texian Leopard - We were shown a few days since the skin of a leopard which was killed near Bexar (San Antonio), some weeks since. The animal to which the skin belonged must have been about ten feet long from the tip of its nose to the end of its tail, and his body of proportional dimensions. The skin is beautifully variegated with black spots, upon a yellowish brown and white ground; and so closely resembles the skin of an African Leopard, that it would be difficult to distinguish it, if found among several skins of that animal. Many persons in the United States have doubted that statements made by travelers that the leopard exists in Texas; but if they could visit Bexar and its vicinity, their skepticism would soon vanish. It is said that great numbers of those Leopards are found in the vicinity of the Nueces and the Rio Grande…

I think it is safe to assume that the “Mexican Lion” in the first account and the “Texian Leopard” described in the second article were almost certainly jaguars. Though the sizes described seem unusually large – mainly in length – every other characteristic mentioned fits the jaguar perfectly (I think the unusual lengths mentioned could be due to the skins of the animals having been measured and not the actual animal). These accounts solidify what we already knew: jaguars were once native to Texas and more numerous in the southern reaches of the state (or in the case of the second account discussed above, the Republic).

I have long felt that jaguars were the number one suspect in the Lone Star State’s black panther mystery. Jaguars fit the size profile most often reported (6+ feet in length nose to tail, 100-150 lbs, etc.), are native to the region, and also can be black (melanistic). The two articles provide more evidence – anecdotal though it may be – that early Texas settlers and residents in the 1800s were encountering jaguars. If so, it is possible a remnant population, one in which melanism has taken hold, lives here still and is responsible for at least some of the black panther sightings that Texans continue to report to this very day.

Now, back home I go. If I beat my wife back to the house, I might add my own little touch to the redecorating. Maybe a nice jaguar mural on one wall would look good…

Source:

Boatright, M. C., & Day, D. (1944). From hell to breakfast. Texas Folk-Lore Society.

The Headless Horseman of the Nueces

Human kind has always been a superstitious lot. Tales of ghosts, monsters, witches, and other “haints” are universal and cross all cultural divides and borders. Especially terrifying are tales where the alleged spectre in question met his/her end in the most gruesome of ways: decapitation. Tales of ghosts cursed to search for their missing heads on this earthly plane abound. One such example of this particular mythos is the tale behind the ghost lights of Bragg Road in East Texas. Some who believe in such things claim the lights are tied to a long dead conductor or railway worker who slipped under the train that used to run along the road and lost his head beneath the wheels of a tanker car or caboose. While all such stories are frightening, the terror seems to ratchet up a notch when the headless spirit is astride an equally ghostly horse. Images of Washington Irving’s Ichabod Crane fleeing for his life from the Headless Horseman of Sleepy Hollow are those most commonly dredged up from the minds of most when the topic is broached. But it is all in good fun, such things are just campfire stories meant to thrill and delight the younger members of families. Headless riders are not real.

Except when they are.

In the mid 1800s, not long after the Mexican-American War wrapped up, settlers around the Nueces River in South Texas began to report sightings of a headless horseman roaming the countryside. Witnesses claimed the rider, dubbed "El Muerto," carried his head (still wearing a sombrero) tied to the horn of his saddle. About his shoulders, the rider wore a brush-torn serape over a buckskin jacket. The legs of the apparition were covered by rawhide leggings of the kind worn by Mexican vaqueros. The horseman was always seen astride a black mustang stallion so wild it seemed to have erupted onto the Texas plains straight from the mouth of hell. The rider was seen both day and night and there seemed to be no pattern to when and where he might appear next. The only constant was that he always rode alone and brought a paralyzing terror to any unlucky enough to lay eyes upon him. The Indians of the region, who rarely agreed with the Anglo settlers on much of anything, concurred that the rider was real and endeavored to keep their distance from him. Tribes on the hunt for bison or wild horses would range hundreds of miles out of their way to avoid entering the territory of the headless spirit.

Mayne Reid, stationed at Fort Inge on the Leona River, wrote, “No one denied that that thing had been seen. The only question was how to account for a spectacle so peculiar as to give the lie to all known laws of creation.” Reid went on to list the many theories that had sprung up in an effort to explain the rider. An Indian dodge, a lay figure, a normal rider disguised with his head beneath a serape that shrouded his shoulders, and the possibility that the headless horseman was none other than Lucifer himself were the most common explanations bandied about by settlers and soldiers in the region. One theory not expounded upon by Reid was that the rider was the patron, or ghostly guard, of the lost mine of the long-abandoned Candelaria Mission on the Nueces River. The debate raged on but the mystery as to the rider’s identity remained.

Finally, a group of settlers – tired of being afraid – managed to ambush the headless horseman at a watering hole near the present day town of Alice. The rider seemed impervious to their firearms. One man in the posse said, “Our bullets passed through him as easily as through a paper target.” A change in tactics was in order and the settlers shifted their fire from the seemingly invulnerable rider to the black mustang. The horse, it seemed, did not share the rider’s ability to weather gunfire and was felled quickly. Upon inspection, the settlers found a desiccated human carcass – one riddled by bullet holes and arrows – lashed to the back of the mustang. The mystery was solved but it birthed another question: who was the headless rider?

It was learned some time later exactly how the headless horseman of the Nueces had come to be. The answer came from none other than legendary Texas Ranger Bigfoot Wallace himself. Years before, during the Texas Revolution, Texian militias laid siege to the city of San Antonio. On the night of December 4, 1835, a Mexican lieutenant named Vidal deserted, joined the Texians, and provided them with valuable intelligence that helped lead to the surrender of the city by General Cos (the Mexican military would later return and avenge their humiliation at the Battle of the Alamo). After the Texians won their independence from Mexico at the Battle of San Jacinto, Vidal took to stealing horses in order to make a living. He proved quite adept at this endeavor and became the head of several rings of horse thieves operating in South Texas. The Texians were slow to suspect Vidal – despite mounting evidence – due to his reputation as a Texas patriot. Vidal was able to further deflect suspicion by deftly planting evidence that suggested the Comanches – who often raided settlements and homesteads for horses – were the true culprits.

Despite his best efforts, a couple of ranchers named Flores and Taylor began to suspect Vidal of the thievery and struck out to follow the trail of the rustlers. While camping on the Frio River, Flores and Taylor met up with Bigfoot Wallace – not one to tolerate a horse thief – who decided to join the hunt. As they drew nearer to the stolen herd, the hunters came across cattle that had been shot with arrows. “Vidal’s trick to make greenhorns smell Indians,” Taylor wrote. The three men did not fall for the ruse and pressed on, finally catching up to Vidal and his men near the Leona, only twelve miles from Fort Inge. To make a long story a bit shorter, the three men sneaked into the rustler’s camp and made short work of Vidal and his men that very night.

The next morning, Wallace – always a bit on the eccentric side – made a faithful decision. He chose a black mustang stallion from the recovered caballada, one that had been herd-broken but never saddled. Wallace roped the stallion, saddled him, and – after decapitating Vidal – lashed the horse thief’s body securely to the mustang. Wallace then laced Vidal’s head, sombrero and all, to the horn of the saddle. The three men then stepped back to admire their work. Before them, the lifeless and headless body of the king of South Texas horse thieves sat bolt upright on the back of a stallion so wild that Satan himself could not ride him. Bigfoot Wallace would declare years later that he had seen many pitching horses, but had never witnessed any other animal act like that black stallion with the dead horse thief on his back. After the mustang had pitched, bucked, snorted, squealed, pawed the air, and reared up and fallen over backwards, it seemed to accept its fate and fled into the Texas wilderness away from its tormentors and into legend.

It is often said that even the hardest to believe legends contain within them a grain of truth. Such is the case with the tale of the Headless Horseman of the Nueces. The witnesses were telling the truth; the rider was real. Perhaps it is a lesson we should recall when confronted with something that seems unbelievable today. Maybe we should pause before dismissing the outrageous claims of a witness who insists they saw a black panther, a wood ape, or some other creature that is not supposed to exist. Maybe we can treat those witnesses with respect and dignity and help them get to the bottom of what they saw.

Well, it’s just a thought.

Source:

Dobie, J. F. (Ed.). (1995). I'll Tell You a Tale - An Anthology. University of Texas Press.

The Lobo Girl of the Devil's River

Even a man who is pure of heart

And says his prayers by night,

May become a wolf when the wolfbane blooms

And the Autumn moon is bright.

The werewolf legend is likely as old as mankind itself. Tales of shape-shifting shamans, skinwalkers, and unfortunate souls who were either cursed or survived an attack by one of these beasts (only to become a monster themselves) appear in nearly every culture to have ever existed on this planet. I am sure that those versed in the science of psychology could share many theories on why this may be so. I, however, tend to believe that there is something more to such stories. Something significant – and very real to those who experienced it – must have taken place at some point; otherwise, the lore of the werewolf would not have survived for these many generations.

What sort of event could lead to the belief that a human being could be transformed into a wolf when the moon is full? Perhaps the legend has its roots in the tales of feral children found in the forests and jungles of the world long after they were presumed dead. Some of these stories are purely fictional, of course. The wolf-suckled twins Romulus and Remus who, according to legend, founded Rome, are one such example. Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book, which details the rescue of the “man cub” Mowgli by a she-wolf who nursed him and raised him as her own, is another. These tales are all well and good, but is there any proof that such a thing has ever really happened? Surprisingly, the answer is yes.

Throughout history, the discovery of feral children has been extremely rare, but it has happened. The previously mentioned Mowgli was inspired by the strange tale of Dina Sanichar who was raised by wolves in India’s Uttar Pradesh jungle. Found by hunters in a wolf’s den in 1867, Sanichar (named by missionaries who later took him in) walked on all fours, would only accept raw meat as food, gnawed on bones to sharpen his teeth, and could not communicate verbally other than producing decidedly wolf-like grunts, barks, and howls. Eventually, Sanichar did learn to walk upright and dress himself; however, he never did learn language and died at the age of 35. Another real-life example of this phenomenon is “Peter the Wild Boy” who was discovered in the forests of Germany in 1725. Believed to have been abandoned by his parents, the boy was estimated to be 11 years old when found. He was unable to speak and loathed wearing clothes. Within a year of his rescue, Peter was shipped off to London where he became the “human pet” of King George I. The wild boy bounded about the King’s court on all fours, which the courtiers of Kensington Palace initially found quite entertaining. It was widely believed that the boy had been raised by wolves or bears due to his behavior. Eventually, the King tired of Peter and shipped him off to a farm in Herfordshire where he was forced to wear a collar that read: “Peter the Wild Man of Hanover. Whoever will bring him to Mr. Fenn at Berhamsted shall be paid for their trouble.” Peter died in 1785 and was buried in the cemetery of St. Mary’s at Northchurch. There are numerous other examples of feral children that were suspected to have been raised by animals that could be cited here, but I trust the point has been made. What many do not realize is that this very scenario may have once played out in the deserts of west Texas.

A nearly forgotten historical fact is that a group of English people once established a small settlement called Delores on the banks of the Devil’s River (part of the Rio Grande drainage basin) in southwest Texas. The community was short-lived as most of the settlers were killed by Comanches. One white couple (who had a rather colorful history of their own), who lived on the extreme edges of the settlement, survived and carried on. One day in 1835, the settler husband frantically rode up to a homestead owned by Mexican goat ranchers and asked for help as his wife was having a baby and was in great distress. According to legend, a storm was brewing and the Mexican couple wanted to wait it out before mounting up and going to the aid of the mother to be. The settler insisted they leave immediately as his wife’s need was great. The Mexican couple relented and they started toward the settler’s home on the Devil’s River. The party had hardly started out when the settler was struck by lightning and killed. This event gave the rancheros pause and they decided to wait until morning to make the trek. While understandable, the decision of the Mexican couple proved disastrous for the female settler. Her lifeless body was found beneath an open brush arbor the next morning. There were clear signs the woman had died during childbirth, yet no child could be found. The couple hastily searched for the infant but found only lobo tracks in the vicinity. The couple assumed that wolves had come upon the scene and devoured the infant. Why the lobos had left the body of the mother unmolested was puzzling to the pair, but they proceeded with burying the unfortunate mother and then made their way home.

Ten years later, in 1845, a boy living at San Felipe Springs (now called Del Rio) reported that he had witnessed a pack of wolves attacking a herd of goats. With them, he claimed, was a long-haired creature that resembled a naked girl. The boy was chastised greatly, but the story – as good tales are apt to do – spread throughout the region. Roughly a year later, a Mexican woman at San Felipe declared she had watched two big lobos and a naked girl ravenously devouring a freshly killed goat. The woman claimed to have gotten very close to this odd trio before they took notice of her and bolted. The naked girl, at first, ran on all fours but eventually rose up and ran on two feet. The woman reported she was positive as to what she had seen and that the child was definitely keeping company with the two wolves.